One of the most common things I get asked about is how to help children who either have an early rising habit, or have a late bedtime. For exhausted parents, tired of having disrupted or stressful evenings, or cripplingly early starts – there is indeed hope!

First of all, infants, children adolescents and adults all have slightly different sleep/wake rhythms and biological clocks. This is colloquially known as the owl/lark tendency, or in the research literature people refer to the ‘eveningness’ (owl) or ‘morningness’ (lark) chronotype (biological or circadian rhythm tendency).

In general, babies are larks. They gradually shift towards an owl circadian rhythm some time between 10-20 years. They then gradually shift back towards a more lark rhythm during adulthood. Which brings us to the idea of owl/lark incompatibility! For some parents, their child is sleeping well, but not at times that dovetail well with their own sleeping patterns and preferences – for example, I am a classic owl: I prefer to go to sleep at around midnight, and wake at around 9am. My children, however, are usually awake by 6.30am. There’s nothing wrong with their sleep quality or duration, but their biological clock is clashing with mine, and I am consequently sleep deprived. For others, there is no question that the time their child either wakes or falls asleep would be clinically classified as a circadian rhythm phase disorder.

So, what affects your circadian rhythm? The key to understanding how to treat early rising or late bedtimes is to be able to correctly figure out what’s going on with the child’s body clock, and be able to manipulate the factors which influence it:

- Eating times

- Light exposure

- Activity

- Temperature

All of the above variables are easy to manipulate and there is a lot of very robust evidence to support the links between all of these environmental, biological and social variables and their influence on circadian rhythmicity.

Essentially, there is a master clock in the brain, which controls several other clocks spread out throughout the body in various organ systems and even at the cellular level. The body clock controls several biological systems that fluctuate over a 24 hour period – including concentration, blood pressure, appetite, sleepiness, and so on. When the body clock is aligned with sleep/wake timings, we feel better, and when there is a mismatch between our body clock and our sleep/wake timings, we feel jet lagged.

Of course, adults can rationalise many of the behaviours that influence the body clock, and make decisions about behaviours which will optimise the circadian rhythm. Children are not able to do this, and therefore require their parents to have the knowledge necessary to help them.

Early rising

For children who wake early – before 6am, there may well be behavioural and other factors that need to be addressed – we’ll have to tackle that stuff another time, or this blog is going to be way too long!

- Review their bedtime. Is your child falling asleep very early – before 7pm? If so, it may be unrealistic to expect them to sleep 11-12 hours overnight. It may be that your little one needs a shorter nighttime sleep and more daytime sleep. Try shifting their bedtime a little later, in small 15 minute increments, to see if this alters the waking time.

- Is your child falling asleep too late? Sometimes an earlier bedtime actually helps, but do this with caution – after all, children can only sleep a certain number of hours in 24! If they’ve had their quota by 5am, then an earlier bedtime will not help. Only try this if you are certain that your child is getting too little sleep overnight in total.

- Make sure your child naps (if age appropriate) right in the middle of their awake period in the day. You neither want your child to nap too soon after waking so that they then have a long awake period before bedtime, or too long after waking so that they are cranky going into the nap, and also do not have long enough time awake before bedtime.

- When your child wakes early, try to keep them in the dark, and do not turn the lights on immediately. If your child is waking at 4.30, wait quietly with them in the dark for 20-30 minutes, then turn the light on and cheerfully (I know this is hard!) say ‘Good morning’, and start the day. This gives your child the message that when it’s light, it’s time to get up. Keep making the time the lights go on and your start the day later and later.

- Try ‘stirring’ your child about 15 minutes before the usual wake up time to see if you can re-boot the sleep cycle and delay the wake up time.

- Do not give your child food until the normal breakfast time. There is an abundance of evidence that eating times strongly influence the circadian rhythm, so try to keep your meal times regular and at sensible times. You may need to do this is slow stages

- If your child falls asleep very early in the evening, then keep the lights on brightly in the evening until 1 hour before your bedtime routine starts. Most people fall asleep about 2 hours after their melatonin (sleepy hormone) begins to rise, which is closely linked to light exposure.

- Expose your child to as much natural bright light as possible, in the daytime. If the light is dim, then keep the lights on, or consider a bright lightbulb in your lamps like this.

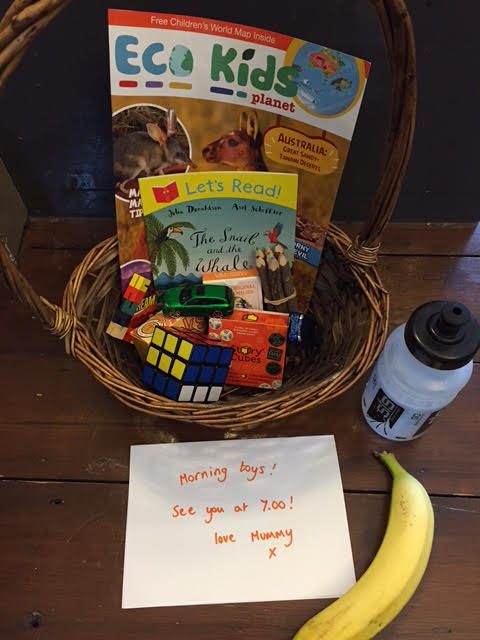

- If your child is old enough, you could try leaving some toys and quiet activities out

A gro-clock alternative?

Many parents use a gro-clock. I have nothing against it if it seems to be working! For those of you not aware, this is a digital clock which does not have a time, but is blue when it’s nighttime, and turns yellow when it’s time to get up. It is supposed to give children the message that they do not get up until the bedtime clock turns yellow and it is therefore morning. It also has some stars around the outside of the clock face which count down until morning. However, there are two main problems with it:

- Many children are not able to count the stars down so this is an over-complicated function

- It emits blue light, which inhibits melatonin

I have an alternative, which is less ambiguous, and does not interfere with melatonin production. Here’s what you do:

- Get a small digital clock with red numbers

- Decide when it is reasonable to allow your child to start their day – let’s say that’s 6am

- Teach your child what the number 6 looks like. Point it out everywhere – on shoes, on signs, in stores

- When they have been exposed a lot to the number 6 (preferably the digital 6!), then point out the number 6 but ask your child to say what number it is. Make it fun and light-hearted.

- When you’re sure your child knows the number 6, you’re ready to move onto the next step

- Write out the number 6 on a piece of paper, and stick it on the clock where the minutes are. Only the hour number should be visible, like this:

- You could also play some number matching snap games to reinforce the concept

- Explain to your child that when they see 2 sixes (the digital one and the one you wrote on the paper) it’s time to get up. What this means is that even if it’s 5.59, the numbers wont match, and it’s therefore not time to get up.

- If you decide to move the numbers forward in half hour increments (which is sensible!), then what you’ll have to do is put the clock back by half an hour so it reads 6am, when it’s actually 6.30

Late bedtimes

For parents who are desperate for some much needed ‘adult time’ or space to recharge their batteries, having a child that wont settle until very late can be extremely frustrating.

- Ensure your child eats at sensible times. Eating too late can really upset your body clock, and also reduce the quality of sleep. Aim for your child to be eating about 2 hours before the intended bedtime (that doesn’t apply to drinks).

- Dim the lights gradually earlier and earlier in the evening. If your child currently goes to bed at 9pm, then dim the lights at 7pm. Then a couple of days later, start dimming at 6.30, and so on, until the lights are being dimmed about 2 hours before your ideal bedtime

- Make sure that your child is not spending along time in their room awake after lights out. This can lead to a faulty sleep hygiene and make the situation worse.

- Try a technique called ‘fading’, where you deliberately put your child to bed late, then slowly inch it earlier. So if your child falls asleep at 9.30pm, start the routine at 9pm, with dim lights from 7pm. Aim for them to be asleep within 20 minutes of the lights out time. Then a couple of days later, dim the lights at 6.30pm, and start the routine at 8.30pm, and so on.

- Ensure your child is waking up at an appropriate time. If they fall asleep late and wake up late, this will reinforce the circadian rhythm that you are struggling with. So wake your child up a little earlier every day and expose them to bright light as soon as they wake up. Keep waking them earlier and earlier, with the light exposure, whilst you also tackle bringing bedtime forward at the same rate.

- Have plenty of light exposure in the day.

- Try cooling the bath down a little in the evening. Really warm baths can make it harder to fall asleep.

- Avoid spicy, sugary and fatty food in the evening especially.

- Consider putting sunglasses on your child in the late afternoon, to try to trick their body clock!

To some extent, your child’s circadian rhythm and their tendency to either be an owl or lark is a little out of your hands, but there is increasing evidence that there are techniques that can and do help to re-align the body clock.

Good luck!

Lyndsey Hookway is a paediatric nurse, health visitor, IBCLC, holistic sleep coach, PhD researcher, international speaker and author of 3 books. Lyndsey is also the Co-founder and Clinical Director of the Holistic Sleep Coaching Program, co-founder of the Thought Rebellion, and founder of the Breastfeeding the Brave project. Check Lyndsey’s speaker bio and talk brochure, as well as book her to speak at your event by visiting this page. All Lyndsey’s books, digital guides, courses and webinars can be purchased here, and you can also sign up for her free monthly newsletter here.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.